Why Particle Physics?

Particle Physics, a field that straddles the line between the known and the unknown, exploring the fundamental particles and forces that form the very fabric of our universe. Doesn’t that sound amazing? You may ask.

Particle physics’ ambition to answer some of the most profound questions humanity has ever posed: What is matter made of? What are the forces that hold our universe together? Could there be particles and phenomena we have not yet discovered? These questions fuel the curiosity of scientists worldwide, drawing many, including myself, into the intricate and often puzzling world of particle research.

Yet, as thrilling as it sounds, the reality of this field is not without its challenges.

20th Century - the Golden Age

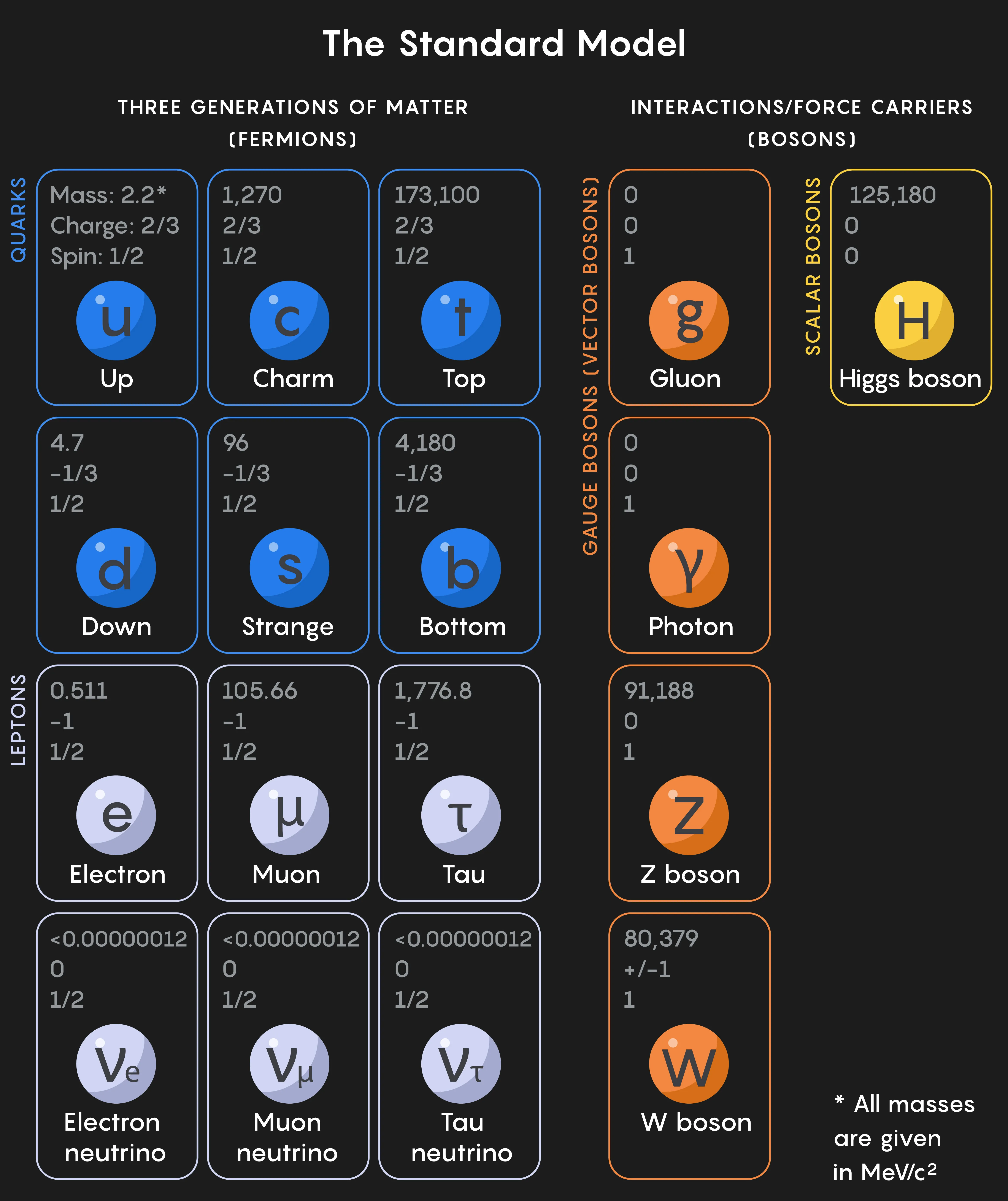

One of the cornerstones of particle physics is the Standard Model (SM) - a robust framework that has successfully described the interactions of fundamental particles through the electromagnetic, weak, and strong forces. The SM is a triumph of modern physics, predicting and explaining a vast range of phenomena with remarkable accuracy. It unifies our understanding of particles like quarks, leptons, and bosons, each contributing to the structure and function of the universe as we know it.

The success of the Standard Model, however, did not come overnight. Throughout the twentieth century, physicists made incremental discoveries that gradually built the model we rely on today.

-

Electron (1897) – The discovery of the electron by J.J. Thomson marked the first identification of a fundamental particle, introducing the concept of subatomic particles to science. This laid the groundwork for future explorations into the nature of matter.

-

Proton and Neutron (1917, 1932) – Ernest Rutherford discovered the proton in 1917, and James Chadwick identified the neutron in 1932. These discoveries refined the model of the atom and introduced the idea of a nucleus with protons and neutrons.

-

Photon (1923) – The photon, the quantum of light, was theorized through Einstein’s work on the photoelectric effect in 1905, and the quantum nature of photons was further validated by experiments in the 1920s.

-

Positron (1932) – The positron, or the electron’s antimatter counterpart, was predicted by Paul Dirac in 1928 and then discovered by Carl Anderson in 1932. This was the first discovery of an antiparticle, hinting at the possibility of a whole “mirror world” of antimatter.

-

Pions and Muons (1947) – In studying cosmic rays, researchers discovered the pion (predicted by Yukawa in 1935) and the muon. These discoveries were unexpected and led to questions about the existence of other types of particles.

-

Quarks (1964) – Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig independently proposed the quark model, which described protons and neutrons as being made up of quarks. The quark model introduced a new way of understanding matter’s structure, though direct evidence for quarks would not come until later.

-

Charm Quark (1974) – The discovery of the charm quark in 1974, known as the “November Revolution,” was a pivotal moment. Detected through the discovery of the J/ψ meson, it confirmed the existence of a new type of quark, validating the quark model.

-

Gluons (1979) – Gluons, the carriers of the strong force that bind quarks together within protons and neutrons, were observed indirectly in high-energy particle collisions at the DESY accelerator in Germany. This completed the theoretical framework of quantum chromodynamics (QCD), describing the strong force.

-

Bottom Quark (1977) and Top Quark (1995) – The bottom quark was discovered at Fermilab in 1977, and the top quark, the heaviest known quark, was discovered in 1995, also at Fermilab. These discoveries helped complete the “quark picture” of matter.

-

W and Z Bosons (1983) – The W and Z bosons, mediators of the weak force, were discovered at CERN, providing the first experimental proof of the electroweak theory. The discovery of these particles solidified the unification of the electromagnetic and weak forces, a major success for the Standard Model.

-

Tau Lepton (1975) – Discovered at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC), the tau was the heaviest lepton, adding another layer to the lepton family and suggesting that particle families might come in triplets.

-

Higgs Boson (2012) – The discovery of the Higgs boson at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) was a monumental achievement. Predicted in the 1960s by Peter Higgs and others, the Higgs boson is associated with the Higgs field, which gives mass to fundamental particles. Its discovery completed the particle roster of the Standard Model.

The culmination of this work came in 2012 with the discovery of the Higgs boson at CERN, completing the particle roster predicted by the Standard Model. This discovery was celebrated worldwide as a landmark achievement and proof of nearly five decades of theoretical development. The SM stood as a crowning achievement of twentieth-century physics—a model of elegance and predictive power.

The theory of everything, right? Right? RIGHT?!!

The Standard Model may be one of our (yes, us, human) most significant achievement, but it is far from our final one.

Despite its remarkable success, the Standard Model leaves us with profound, unanswered questions. For all its elegance, it is not the “theory of everything” that physicists have dreamed of. Gravity, for instance, remains an outlier. Unlike the other three fundamental forces, it has no place in the Standard Model. This omission points to one of the deepest mysteries in physics: why gravity, so vital on cosmic scales, seems so elusive in the quantum realm.

Then there is the enigma of dark matter and dark energy. Observations show that ordinary matter—the stuff that makes up stars, planets, and galaxies - composes less than five percent of the universe. The rest? Is it dark matter and dark energy, invisible forces that the Standard Model does not even begin to address? Dark matter interacts with visible matter through gravity, and though we know it exists, we have no idea what it is made of. Dark energy, on the other hand, drives the accelerating expansion of the universe, a phenomenon that challenges our understanding of cosmology and the laws of physics themselves.

This gap between what we can describe and what remains hidden is both humbling and exhilarating. Physicists believe that to answer these questions, we may need a new framework, one that goes beyond the Standard Model. Theories like supersymmetry and string theory attempt to fill these gaps, but they remain speculative without experimental evidence to support them for decades.

Is the answer to build ever-more-powerful particle accelerators, detectors, and telescopes, hoping to glimpse something unexpected that might illuminate these mysteries? Or is it to measure with ever-more-precise instruments, refining our observations of the universe until we capture the subtle discrepancies that hint at new physics?

to be continued…